|

The

Smokey God, or A Voyage to the Inner World |

As

told to Willis George Emersom

"He is the God who sits in the center, on the navel of the earth, and he is

the interpreter of the religion to all mankind." - Plato. PART ONE:

AUTHOR'S FOREWORD I fear the seemingly incredible story which I am about to

relate will be regarded as the result of a distorted intellect superinduced,

possibly, by the glamour of unveiling a marvelous mystery, rather than a

truthful record of the unparalleled experiences related by one Olaf Jansen,

whose eloquent madness so appealed to my imagination that all thought of an

analytical criticism has been effectually dispelled. Marco Polo will doubtless

shift uneasily in his grave at the strange story I am called upon to chronicle;

a story as strange as a Munchausen tale. It is also incongruous that I, a

disbeliever, should be the one to edit the story of Olaf Jansen, whose name is

now for the first time given to the world, yet who must hereafter rank as one of

the notables of earth. I freely confess his statements admit of no rational

analysis, but have to do with the profound mystery concerning the frozen North

that for centuries has claimed the attention of scientists and laymen alike.

However much they are at variance with the cosmographical manuscripts of the

past, these plain statements may be relied upon as a record of the things Olaf

Jansen claims to have seen with his own eyes. A hundred times I have asked

myself whether it is possible that the world's geography is incomplete, and that

the startling narrative of Olaf Jansen is predicated upon demonstrable facts.

The reader may be able to answer these queries to his own satisfaction, however

far the chronicler of this narrative may be from having reached a conviction.

Yet sometimes even I am at a loss to know whether I have been led away from an

abstract truth by the [Italic]ignes fatui[No Italic] of a clever superstition,

or whether heretofore accepted facts are, after all, founded upon falsity. It

may be that the true home of Apollo was not at Delphi, but in that older

earth-center of which Plato speaks, where he says: "Apollo's real home is

among the Hyperboreans, in a land of perpetual life, where mythology tells us

two doves flying from the two opposite ends of the world met in this fair region,

the home of Apollo. Indeed, according to Hecataeus, Leto, the mother of Apollo,

was born on an island in the Arctic Ocean far beyond the North Wind." It is

not my intention to attempt a discussion of the theogony of the deities nor the

cosmogony of the world. My simple duty is to enlighten the world concerning a

heretofore unknown portion of the universe, as it was seen and described by the

old Norseman, Olaf Jansen. Interest in northern research is international.

Eleven nations are engaged in, or have contributed to, the perilous work of

trying to solve Earth's one remaining cosmological mystery. There is a saying,

ancient as the hills, that "truth is stranger than fiction," and in a

most startling manner has this axiom been brought home to me within the last

fortnight. It was just two o'clock in the morning when I was aroused from a

restful sleep by the vigorous ringing of my door-bell. The untimely disturber

proved to be a messenger bearing a note, scrawled almost to the point of

illegibility, from an old Norseman by the name of Olaf Jansen. After much

deciphering, I made out the writing, which simply said: "Am ill unto death.

Come." The call was imperative, and I lost no time in making ready to

comply. Perhaps I may as well explain here that Olaf Jansen, a man who quite

recently celebrated his ninety-fifth birthday, has for the last half-dozen years

been living alone in an unpretentious bungalow out Greendale way, a short

distance from the business district of Los Angeles, California. It was less then

two years ago, while out walking one afternoon, that I was attracted by Olaf

Jansen's house and it's homelike surroundings, toward its owner and occupant,

whom I afterward came to know as a believer in the ancient worship of Odin and

Thor. There was a gentleness in his face, and a kindly expression in the keenly

alert grey eyes of this man who had lived more than four-score years and ten;

and, withal, a sense of loneliness that appealed to my sympathy. Slightly

stooped, and with his hands clasped behind him, he walked back and forth with

slow and measured tread, that day when first we met. I can hardly say what

particular motive impelled me to pause in my walk and engage him in conversation.

He seemed pleased when I complimented him on the attractiveness of his bungalow,

and on the well-tended vines and flowers clustering in profusion over its

windows, roof and wide piazza. I soon discovered that my new acquaintance was no

ordinary person, but one profound and learned to a remarkable degree; a man who,

in the later years of his long life, had dug deeply into books and become strong

in the power of meditative silence. I encouraged him to talk, and soon gathered

that he had resided only six or seven years in Southern California, but had

passed the dozen years prior in one of the middle Eastern states. Before that he

had been a fisherman off the coast of Norway, in the region of the Lofoden

Islands, from whence he had made trips still farther north to Spitzbergen and

even to Franz Josef Land. When I started to make my leave, he seemed reluctant

to have me go, and asked me to come again. Although at the time I thought

nothing of it, I remember now that he made a peculiar remark as I extended my

hand in leave-taking. "You will come again?" he asked. "Yes, you

will come again some day. I am sure you will; and I shall show you my library

and tell you many things of which you have never dreamed, things so wonderful

that it may be you will not believe me." I laughingly assured him that I

would not only come again, but would be ready to believe whatever he might

choose to tell me of his travels and adventures. In the days that followed I

became well acquainted with Olaf Jansen, and, little by little, he told me his

story, so marvelous, that its very daring challenges reason and belief. The old

Norseman always expressed himself with so much earnestness and sincerity that I

became enthralled by his strange narrations. Then came the messengers's call

that night, and within the hour I was at Olaf Junsen bungalow. He was very

impatient at the long wait, although after being summoned I had come immediately

to his bedside. "I must husten", he exclaimed, while yet he held my

hand in greeting. "I have much to tell you that you know not, and I will

trust no one but you. I fully realize," he went on hurriedly, "that I

shall not survive the night. The time has come to join my fathers in the great

sleep." I adjusted the pillows to make him more comfortable, and assured

him I was glad to be able to serve him in any way possible, for I was begining

to realize the seriousness of his condition. The lateness of the hour, the

stillness of the surroundings, the uncanny feeling of being alone with the dying

man, together with his weird story, all combined to make my heart beat fast and

loud with a feeling for which I have no name. Indeed, there were many times that

night by the old Norseman's couch, and there have been many times since, when a

sensation rather than a conviction took posession of my very soul, and I seemed

not only to believe in, but actually see, the strange lands, the strange people

and the strange world of which he told, and to hear the mighty orchestral chorus

of a thousand lusty voices. For over two hours he seemed endowed with almost

superhuman strength, talking rapidly, and to all appearances, rationally.

Finally he gave me into my hands certain data, drawings and crude maps. "These,"

said he in conclusion, "I leave in your hands. If I can have your promise

to give them to the world, I shall die happy, because I desire that people may

know the truth, for then all mystery concerning the frozen Northland will be

explained. There is no chance of your suffering the fate I suffered. They will

not put you in irons, nor confine you in a mad-house, because you are not

telling your own story, but mine, and I, thanks to the gods, Odin and Thor, will

be in my grave, and so beyond the reach of disbelievers who would persecute."

Without a thought of the far-reaching results the promise entailed, or

foreseeing the many sleepless nights which the obligation has since brought me,

I gave my hand and with it a pledge to discharge faithfully his dying wish. As

the sun rose over the peaks of the San Jacinto, far to the eastward, the spirit

of Olaf Jansen, the navigator, the explorer and worshiper of Odin and Thor, the

man whose experiences and travels, as related, are without a parallel in the

world's history, passed away, and I was left alone with the dead. And now, after

having paid the last sad rites to this strange man from the Lofoden Islands, and

the still farther "Northward Ho!", the courageous explorer of frozen

regions, who in his declining years (after he had passed the four-score mark)

had sought an asylum of restful peace in sunfavored California, I will undertake

to make public his story. But, first of all, let me indulge in one or two

reflections: Generation follows generation, and the traditions from the misty

past are handed down from sire to son, but for some strange reason interest in

the ice-locked unknown does not abate with the receding years, either in the

minds of the ignorant or the tutored. With each new generation a restless

impulse stirs the hearts of men to capture the veiled citadel of the Arctic, the

circle of silence, the land of glaciers, cold wastes of waters and winds that

are strangely warm. Increasing interest is manifested in mountainous icebergs,

and marvelous speculations are indulged in concerning the earth's center of

gravity, the cradle of the tides, where the whales have their nurseries, where

the magnetic neddle goes mad, where the Aurora Borealis illumines the night, and

where brave and courageous spirits of every generation dare to venture and

explore, defying the dangers of the "Farthest North." One of the

ablest works of recent years is "Paradise Found, or the Cradle of The Human

Race at the North Pole," by William F. Warren. In his carefully prepared

volume, Mr. Warren almost stubbed his toe against the real truth, but missed it

seemingly by only a hair's breadth, if the old Norseman's revelation be true.

Dr. Orville Livingston Leech, scientist, in a recent article, says: [Iatlic]

"The possibilities of land inside the earth were first brought to my

attention when I picked up a geode on the shores of the Great Lakes. The geode

is a spherical and apparently solid stone, but when broken is found to be hollow

and coated with crystals. The earth is only a large form of geode, and the law

that created the geode in its hollow form undoubtedly fashioned the earth in the

same way." [No Italic] In presenting the theme of this almost incredible

story, as told by Olaf Jansen, and supplemented by manuscript, maps and crude

drawings entrusted to me, a fitting introduction is found in the following

qoutation: "In the beginnig God created the heaven and the earth, and the

earth was without form and void." And also, "God created man in his

own image." Therefore, even in things material, man must be God-like,

because he is in the likeness of the Father. A man builds a house for himself

and family. The porches or verandas are all without, and are secondary. The

building is really constructed for conveniences within. Olaf Jansen makes the

startling announcement through me, an humble instrument, that in like manner,

God created the earth for the "within" - that is to say, for its lands,

seas, rivers, mountains, forests and valleys, and for its other internal

conveniences, while the outside surface of the earth is merely the veranda, the

porch, where things grow by comparison but sparsely, like the lichen on the

mountain side, clinging determinedly for bare existance. Take an egg-shell, and

from each end break out a piece as large as the end of this pencil. Extract its

contents, and then you will have a perfect representation of Olaf Jansen's earth.

The distance from the inside surface to the outside surface, according to him,

is about three hundred miles. The center of gravity is not in the center of the

earth, but in the center of the shell or crust; therefore, if the thickness of

the earth's crust or shell is three hundred miles, the center of gravity is one

hundred and fifty miles below the surface. In their log-books Arctic explorers

tell us of the dipping of the needle as the vessel sails in regios of the

farthest north known. In reality, they are at the curve; on the edge of the

shell, where gravity is geometrically increased, and while the electric current

seemingly dashes off into space toward the phantom idea of the North Pole, yet

this same electric current drops again and continues its course southward along

the inside surface of the earth's crust. In the appendix to his work, Captain

Sabine gives an account of experiments to determine the acceleration of the

pendulum in different latitudes. This appears to have resulted from the joint

labor of Peary and Sabine. He sais: "The accidental discovery that a

pendulum on being removed from Paris to the neighborhood of the equator

increased its time of vibration, gave the first step to our present knowledge

that the polar axis of the globe is less than equatorial; that the force of

gravity at the surface of the earth increases progressively from the equator

toward the poles." According to Olaf Jansen, in the beginning this old

world of ours was created solely for the "within" world, where are

located the four great rivers - the Euphrates, the Pison, the Gihon and the

Hiddekel. These same names of rivers, when applied to streams on the "outside"

surface of the earth, are purely traditional from an antiquity beyond the memory

of man. On the top of a high mountain, near the fountain-head of this four

rivers, Olaf Jansen, the Norseman, claims to have discovered the long-lost

"Garden of Eden," the veritable navel of the earth, and to have spent

over two years studying and reconnoitering in this marvelous "within"

land, exuberant with stupendous plant life and abounding in giant animals; a

land where the people live to be centuries old, after the order of Methuselah

and other Biblical characters; a region where one-quarter of the "inner"

surface is water and three-quarters land; where there are large oceans and many

rivers and lakes; where modes of transportation are as far in advance of ours as

we with our boasted achievements are in advance of the inhabitants of "darkest

Africa." The distance directly across the space from inner surface to inner

surface is about six hundred miles less then the recognized diameter of the

earth. In the identical center of this vast vacuum is the seat of electricity -

a mammoth ball of dull red fire - not startlingly brilliant, but surrounded by a

white, mild, luminous cloud, giving out uniform warmth, and held in its place in

the center of this internal space by the immutable law of gravitation. This

electrical cloud is known to the people "within" as the abode of

"The Smoky God." They believe it to be the throne of "The Most

High." Olaf Jansen reminded me of how, in the old college days, we were all

familiar with the labaratory demonstrations of centrifugal motion, which clearly

proved that, if the earth was a solid, the rapidity of its revolution upon its

axis would tear it into a thousand fragments. The old Norseman also maintained

that from the farthest points of land on the islands of Spitzbergen and Franz

Josef Land, flocks of geese may be seen annually flying still farther northward,

just as the sailors and explorers record in their log-books. No scientist has

yet been audacious enough to attempt to explain, even to his own satisfaction,

toward what lands these winged fowls are guided by their subtle instinct.

However, Olaf Jansen has given us a most reasonable explanation. The presence of

the open sea in the Northland is also explaind. Olaf Jansen claims that the

northern aperture, intake or hole, so to speak, is about fourteen hundred miles

across. In connection with this, let us read what Explorer Nansen writes, on

page 288 of his book: "I have never had such a splendid sail. On to the

north, steadily north, with a good wind, as fast as stream and sail can take us,

an open sea mile after mile, watch after watch, through these unknown regions,

always clearer and clearer of ice, one might almost say: 'How long will it last?'

The eye always turns to the northward as one paces the bridge. It is gazing into

the future. But there is always the same dark sky ahead which means open sea."

Again, the Norwood Review of England, in its issue of May 10, 1884, says: "We

do not admit that there is ice up to the Pole - once inside the great ice

barrier, a new world breaks upon the explorer, the climat is mild like that of

England, and, afterward, balmy as the Greek Isles." Some of the rivers

"within," Olaf Jansen claims, are large then our Mississippi and

Amazon rivers combined, in point of volume of water carried; indeed their

greatness is occasioned by their width and depth rather than their length, and

it is at the mouths of these mighty rivers, as they flow northward and southward

along the inside surface of the earth, that mammoth icebergs are found, some of

them fifteen and twenty miles wide and from forty to one hundred miles in length.

Is it not strange that there has never been an iceberg encountered either in the

Arctice or Antarctic Ocean that is not composed of fresh water? Modern

scientists claim that freezing eliminates the salt, but Olaf Jansen claims

differently. Ancient Hindoo, Japanese and Chinese writings, as well as

hieroglyphics of the extinct races of the North American continent, all speak of

the custom of sun- worshiping, and it is possible, in the startling light of

Olaf Jansen's revelations, that the people of the inner world, lured away by

glimpses of the sun as it shone upon the inner surface of the earth, either from

the northern or the southern opening, became dissatisfied with "The Smoky

God," the great pillar or mother cloud of electricity, and, weary of their

continuously mild and pleasant atmosphere, followed the brighter light, and were

finally led beyond the ice belt and scattered over the "outer" surface

of the earth, through Asia, Europe, North America and, later, Africa, Australia

and South America[Footnote]. [Footnote begin, Italic] The following quotation is

significant; "It follows that man issuing from a mother-region still

undertermined but which a number of considerations indicate to have been in the

North, has radiated in several directions; that his migrations have been

constantly from North to South." - M. le Marquis G. de Saporta, in Popular

Science Montly, October, 1883, page 753. [Footnote end, No Italic] It is a

notable fact that, as we approach the Equator, the stature of the human race

grows less. But the Patagonians of the South America are probably the only

aborigines from the center of the earth who came out through the aperture

usually designated as the South Pole, and they are called the giant race. Olaf

Jansen avers that, in the beginning, the world was created by the Great

Architect of the Universe, so that man might dwell upon its "inside"

surface, which has ever since beeb the habitation of the "chosen."

They who were driven out of the "Garden of Eden" brought their

traditional history with them. The history of the people living "within"

contains a narrative suggesting the story of Noah and the ark with which we are

familiar. He sailed away, as did Columbus, from a certain port, to a strange

land he had heard of far to the northward, carrying with him all manner of

beasts of the fields and fowls of the air, but was never heard of afterward. On

the northern boundaries of Alaska, and still more frequently on Siberian coast,

are found bone-yards containing tusks of ivory in quantities so great as to

suggest the burying-places of antiquity, From Olaf Jansen's account, they have

come from the great prolific animal life that abounds in the fields and forests

and on the banks of numerous rivers of the Inner World. The materials were

caught in the ocean currents, or carried on ice-floes, and have accumulated like

driftwood on the Siberian coast. This has been going on for ages, and hence

these mysterious bone-yards. On this subject William F. Warren, in his book

already cited, pages 297 and 298, says: "The Arctic rocks tell of a lost

Atlantis more wonderful than Plato's. The fossil ivory beds of Siberia excel

everything of the kind in the world. From the days of Pliny, at least, they have

constantly been undergoing exploitation, and still they are the chief

headquarters of supply. The remains of mammoths are so abundant that, as

Gratacap says, 'the northern islands of Siberia seem built up of crowded bones.'

Another scientific writer, speaking of the islands of New Siberia, northward of

the mouth of the River Lena, uses this language: 'Large quantities of ivory are

dug out of the ground every year. Indeed, some of the islands are believed to be

nothing but an accumulation of drift-timber and the bodies of mammoths and other

antediluvian animals frozen together.' From this we may infer that, during the

years that have elapsed since the Russian conquest of Siberia, useful tusks from

more than twenty thousand mammoths have been collected." But now for the

story of Olaf Jansen. I give it in detail, as set down by himself in manuscript,

and woven into the tale, just as he placed them are certain quotations from

recent works on Arctic exploration, showing how carefully the old Norseman

compared with his own experiences those of other voyagers to the frozen North.

Thus wrote the disciple of Odin and Thor:

PART

TWO: OLAF JANSEN'S STORY My name is Olaf Jansen. I am a Norwegian, although I

was born in the little seafaring Russian town of Uleaborg, on the eastern coast

of the gulf of Bothnia, the northern arm of the Baltic Sea. My parents were on a

fishing cruise in the Gulf of Bothnia, and put into this Russian town of

Uleaborg at the time of my birth, being the twenty-seventh day of October, 1811.

My father, Jens Jansen, was born at Rodwig on the Scandinavian coast, near the

Lofoden Islands, but after marrying made his home at Stockholm, because my

mother's people resided in that city. When seven years old, I began going with

my father on his fishing trips along the Scandinavian coast. Early in life I

displayed an aptitude for books, and at the age of nine years was placed in a

private school in Stockholm, remaining there until I was fourteen. After this I

made regular trips with my father on all his fishing voyages. My father was a

man fully six feet three in height, and weighed over fifteen stone, a typical

Norseman of the most rugged sort, and capable of more endurance than any other

man I have ever known. He possessed the gentleness of a woman in tender little

ways, yet his determination and will-power were beyond description. His will

admitted of no defeat. I was in my nineteenth year when we started on what

proved to be our last trip as fishermen, and which resulted in the strange story

that shall be given to the world, - but not until I have finished my earthly

pilgrimage. I dare not allow the facts as I know them to be published while I am

living, for fear of further humiliation, confinement and suffering. First of

all, I was put in irons by the captain of the whaling vessel that rescued me,

for no other reason than that I told the truth about the marvelous discoveries

made by my father and myself. But this was far from being the end of my

tortures. After four years and eight months' absence I reached Stockholm, only

to find my mother had died the previous year, and the property left by my

parents in the possession of my mother's people, but it was at once made over to

me. All might have been well, had I erased from my memory the story of our

adventure and of my father's terrible death. Finally, one day I told the story

in detail to my uncle, Gustaf Osterlind, a man of considerable property, and

urged him to fit out an expedition for me to make another voyage to the strange

land. At first I thought he favored my project. He seemed interested, and

invited me to go before certain officials and explain to them, as I had to him,

the story of our travels and discoveries. Imagine my disappointment and horror

when, upon the conclusion of my narrative, certain papers were signed by my

uncle, and, without warning, I found myself arrested and hurried away to dismal

and fearful confinement in a madhouse, where I remained for twenty-eight years -

long, tedious, frightful years of suffering! I never ceased to assert my sanity,

and to protest against the injustice of my confinement. Finally, on the

seventeenth of October, 1862, I was released. My uncle was dead, and the friends

of my youth were now strangers. Indeed, a man over fifty years old, whose only

known record is that of a madman, has no friends. I was at a loss to know what

to do for a living, but instinctively turned toward the harbor where fishing

boats in great numbers were anchored, and within a week I had shipped with a

fisherman by the name of Yan Hansen, who was starting on a long fishing cruise

to the Lofoden Islands. Here my earlier years of training proved of the very

greatest advantage, especially in enabling me to make myself useful. This was

but the beginning of other trips, and by frugal economy I was, in a few years,

able to own a fishing-brig of my own. For twenty-seven years thereafter I

followed the sea as a fisherman, five years working for others, and the last

twenty-two for myself. During all these years I was a most diligent student of

books, as well as a hard worker at my business, but I took great care not to

mention to anyone the story concerning the discoveries made by my father and

myself. Even at this late day I would be fearful of having any one see or know

the things I am writing, and the records and maps I have in my keeping. When my

days on earth are finished, I shall leave maps and records that will enlighten

and, I hope, benefit mankind. The memory of my long confinement with maniacs,

and all the horrible anguish and sufferings are too vivid to warrant my taking

further chances. In 1889 I sold out my fishing boats, and found I had

accumulated a fortune quite sufficient to keep me the remainder of my life. I

then came to America. For a dozen years my home was in Illinois, near Batavia,

where I gathered most of the books in my present library, though I brought many

choice volumes from Stockholm. Later, I came to Los Angeles, arriving here March

4, 1901. The date I well remember, as it was President McKinley's second

inauguration day. I bought this humble home and determined, here in the privacy

of my own abode, sheltered by my own vine and fig-tree, and with my books about

me, to make maps and drawings of the new lands we had discovered, and also to

write the story in detail from the time my father and I left Stockholm until the

tragic event that parted us in the Antarctic Ocean. I well remember that we left

Stockholm in our fishing-sloop on the third day of April, 1829, and sailed to

the southward, leaving Gothland Island to the left and Oeland Island to the

right. A few days later we succeeded in doubling Sandhommar Point, and made our

way through the sound which separates Denmark from Scandinavian coast. In due

time we put in at the town of Christiansand, where we rested two days, and then

started around the Scandinavian coast to the westward, bound for the Lofoden

Islands. My father was in high spirit, because of the excellent and gratifying

returns he had received from our last catch by marketing at Stockholm, instead

of selling at one of the seafaring towns along the Scandinavian coast. He was

especially pleased with the sale of some ivory tusks that he had found on the

west coast of Franz Joseph Land during one of his northern cruises the previous

year, and he expressed the hope that this time we might again be fortunate

enough to load our little fishing-sloop with ivory, instead of cod, herring,

mackerel and salmon. We put in at Hammerfest, latitude seventy-one degrees and

forty minutes, for a few days' rest. Here we remained one week, laying in an

extra supply of provisions and several casks of drinking-water, and then sailed

toward Spitzbergen. For the first few days we had an open sea and favoring wind,

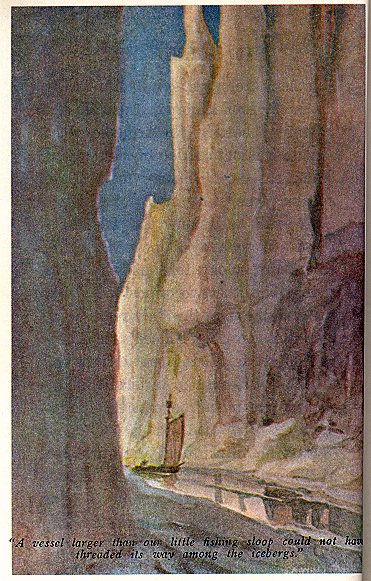

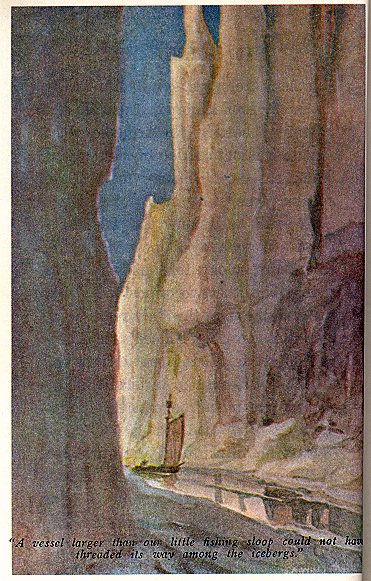

and then we encountered much ice and many icebergs. A vessel large than our

little fishing-sloop could not possibly have threaded its way among the

labyrinth of icebergs or squeezed through the barely open channels. These

monster bergs presented an endless succession of crystal palaces, of massive

cathedrals and fantastic mountain ranges, grim and sentinel-like, immovable as

some towering cliff of solid rock, standing silent as sphinx, resisting the

restless waves of a fretful sea. After many narrow escapes, we arrived at

Spitzbergen on the 23d of June, and anchored at Wijade Bay for a short time,

where we were quite succesful in our catches. We then lifted anchor and sailed

through the Hinlopen Strait, and coasted along the North-East-Land[Footnote].

[Footnote begin, Italic] It will be remembered that Andree started on his fatal

balloon voyage from the northwest coast of Spitzbergen. [Footnote end, No

Italic] A strong wind came up from the southwest, and my father said that we had

better take advantage of it and try to reach Franz Josef Land, where, the year

before he had, by accident, found the ivory tusks that had brought him such a

good price at Stockholm. Never, before or since, have I seen so many sea-fowl;

they were so numerous that they hid the rocks on the coast line and darkened the

sky. For several days we sailed along the rocky coast of Franz Josef Land.

Finally, a favoring wind came up that enabled us to make the West Coast, and,

after sailing twenty-four hours, we came to a beautiful inlet. One could hardly

believe it was the Northland. The place was green with growing vegetation, and

while the area did not comprise more than one or two acres, yet the air was warm

and tranquil. It seemed to be at that point where the Gulf Stream's influence is

most keenly felt[Footnote]. [Footnote begin, Italic] Sir John Barrow, Bart.,

F.R.S., in his work entitled "Voyages of Discovery and Research Within the

Arctic Regions," says on page 57: "Mr. Beechey refers to what has

frequently been found and noticed - the mildness of the temperature on the

western coast of Spitzbergen, there being little or no sensation of cold, though

the thermometer might be only a few degrees above the freezing-point. The

brilliant and lively effect of a clear day, when the sun shines forth with a

pure sky, whose azure hue is so intense as to find no parallel even in the

boasted Italian sky." [Footnote end, No Italic] On the east coast there

were numerous icebergs, yet here we were in open water. Far to the west of us,

however, were icepacks, and still farther to the westward the ice appeared like

ranges of low hills. In front of us, and directly to the north, lay an open sea

[Footnote]. [Footnote begin, Italic] Captain Kane, on page 299, quoting from

Morton's Journal, the 26th of December, says: "As far as I could see, the

open passages were fifteen miles or more wide, with sometimes mashed ice

separating them. But it is all small ice, and I think it either drives out to

the open space to the north or rots and sinks, as I could see none ahead to the

north." [Footnote end, No Italic] My father was an ardent believer in Odin

and Thor, and had frequently told me they were gods who came from far beyond the

"North Wind." There was a tradition, my father explained, that still

farther northward was a land more beautiful than any that mortal man had ever

known, and that it was inhabited by the "Chosen[Footnote]." [Footnote

begin, Italic] We find the following in "Deutsche Mythologie," page

778, from the pen of Jakob Grimm;"Then the sons of Bor built in the middle

of the universe the city called Asgard, where dwell the gods and their kindred,

and from that abode work out so many wondrous things both on the earth and in

the heavens above it. There is in that city a place called Hlidskjalf, and when

Odin is seated there upon his lofty throne he sees over the whole world and

discerns all the actions of men." [Footnote end, No Italic] My youthful

imagination was fired by the ardor, zeal and religious fervor of my good father,

and I exclaimed: "Why not sail to this goodly land? The sky is fair, the

wind favourable and the sea open." Even now I can see the expression of

pleasurable surprise on his countenance as he turned toward me and asked:

"My son, are you willing to go with me and explore - to go far beyond where

man has ever ventured?" I answered affirmatively. "Very well," he

replied. "May the god Odin protect us!" and, quickly adjusting the

sails, he glanced at our compass, turned the prow in due northerly direction

through an open channel, and our voyage had begun [Footnote]. [Footnote begin,

Italic] Hall writes, on page 288: "On 23rd of January the two Esquimaux,

accompanied by two of the seamen, went to Cape Lupton. They reported a sea of

open water extending as far as the eye could reach." [Footnote end, No

Italic] The sun was low in the horizon, as it was still the early summer.

Indeed, we had almost four months of day ahead of us before the frozen night

could come on again. Our little fishing-sloop sprang forward as if eager as

ourselves for adventure. Within thirty-six hours we were out of sight of the

highest point on the coast line of Franz Josef Land. We seemed to be in a strong

current running north by northeast. Far to the right and to the left of us were

icebergs, but our little sloop bore down on the narrows and passed through

channels and out into open seas - channels so narrow in places that, had our

craft been other then small, we never could have gotten through. On the third

day we came to an island. Its shores were washed by an open sea. My father

determined to land and explore for a day. This new land was destitute of timber,

but we found a large accumulation of drift-wood on the northern shore. Some of

the trunks of the trees were forty feet long and two feet in diameter[Footnote].

[Footnote begin, Italic] Greely tells us in vol. 1, page 100, that:

"Privates Connell and Frederick found a large coniferous tree on the beach,

just above the extreme high-water mark. It was nearly thirty inches in

circumference, some thirty feet long, and had apparently been carried to that

point by a currrent within a couple of years. A portion of it was cut up for

fire-wood, and for the first time in that valley, a bright, cheery camp-fire

gave comfort to man." [Footnote end, No Italic] After one day's exploration

of the coast line of this island, we lifted anchor and turned our prow to the

north in an open sea[Footnote]. [Footnote begin, Italic] Dr. Kane says, on page

379 of his works: "I cannot imagine what becomes of the ice. A strong

current sets in constantly to the north; but, from altitudes of more than five

hundred feet, I saw only narrow strips of ice, with great spaces of open water,

from ten to fifteen miles in breadth, between them. It must, therefore, either

go to an open space in the north, or dissolve." [Footnote end, No Italic] I

remember that neither my father nor myself had tasted food for almost thirty

hours. Perhaps this was because of the tension of excitement about our strange

voyage in waters farther north, my father said, than anyone ever before been.

Active mentality had dulled the demands of the physical needs. Instead of cold

being intense as we had anticipated, it was really warmer and more pleasant than

it had been while in Hammerfest on the north coast of Norway, some six weeks

before[Footnote]. [Footnote begin, Italic] Captain Peary's second voyage relates

another circumstance which may serve to confirm a conjecture which has long been

maintained by some, that an open sea, free of ice, exists at or near the Pole.

"On the second of November," says Peary, "the wind freshened up

to a gale from north by west, lowered the thermometer before midnight to 5

degrees, whereas, a rise of wind at Melville Island was generally accompanied by

a simultaneous rise in the thermometer at low temperatures. May not this,"

he asks, "be occasioned by the wind blowing over an open sea in the quarter

from which the wind blows? And tend to confirm the opinion that at or near the

Pole an open sea exists?" [Footnote end, No Italic] We both frankly

admitted that we were very hungry, and forthwith I prepared a substantial meal

from our well-stored larder. When we had partaken heartily of the repast, I told

my father I believed I would sleep, as I was beginning to feel quite drowsy.

"Very well," he replied, "I will keep the watch." I have no

way to determine how long I slept; I only know that I was rudely awakened by a

terrible commotion of the sloop. To my surprise, I found my father sleeping

soundly. I cried out lustily to him, and starting up, he sprang quickly to his

feet. Indeed, had he not instantly clutched the rail, he would certainly have

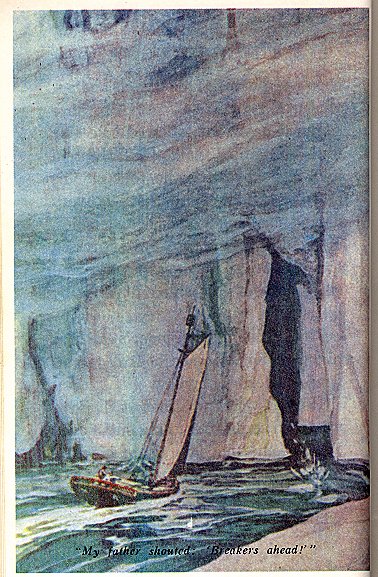

been thrown into the seething waves. A fierce snow-storm was raging. The wind

was directly astern, driving our sloop at a terrific speed, and was threatening

every moment to capsize us. There was no time to lose, the sails had to be

lowered immediately. Our boat was writhing in convulsions. A few icebergs we

knew were on either side of us, but fortunately the channel was open directly to

the north. But would it remain so? In front of us, girding the horison from left

to right, was a vaporish fog or mist, black as Egyptian night at the water's

edge, and white like a steam-cloud toward the top, which was finally lost to

view as it blended with the great white flakes of falling snow. Whether it

covered a treacherous iceberg, or some other hidden obstacle against which our

little sloop would dash and send us to a watery grave, or was merely the

phenomenon of an Arctic fog, there was no way to determine[Footnote]. [Footnote

begin, Italic] On the page 284 of his works, Hall writes: "From the top of

Providence Berg, a dark fog was seen to the north, indicating water. At 10 a.m.

three of the men (Kruger, Nindemann and Hobby) went to Cape Lupton to ascertain

if possible the extent of the open water. On their return they reported several

open spaces and much young ice - not more than a day old, so thin that it was

easily broken by throwing pieces of ice upon it." [Footnote end, No Italic]

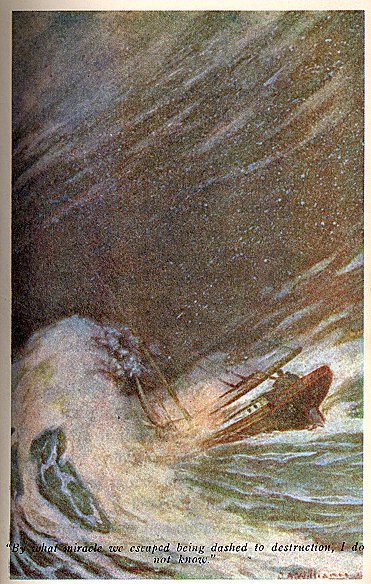

By what miracle we escaped being dashed to utter destruction, I do not know. I

remember our little craft creaked and groaned, as if its joints were breaking.

It rocked and staggered to and fro as if clutched by some fierce undertow of

whirlpool or maelstrom. Fortunately our compass had been fastened with long

screws to a cross-beam. Most of our provisions, however, were tumbled out and

swept away from the deck of the cuddy, and had we not taken the precaution at

the very beginning to tie ourselves firmly to the masts of the sloop, we should

have been swept into the lashing sea. Above the deafening tumult of the raging

waves, I heard my father's voice. "Be courageous, my son," he shouted,

"Odin is the god of the waters, the companion of the brave, and he is with

us. Fear not." To me it seemed there was no possibility of our escaping a

horrible death. The little sloop was shipping water, the snow was falling so

fast as to be blinding,and the waves were tumbling over our counters in reckless

white-sprayed fury. There was no telling what instant we should be dashed

against some drifting icepack. The tremendous swells would heave us up to the

very peaks of mountainous waves, then plunge us down into the depths of the

sea's trough as if our fishing-sloop were a fragile shell. Gigantic white-capped

waves, like veritable walls, fenced us in, fore and aft. This terrible

nerve-racking ordeal, with its nameless horrors of suspense and agony of fear

indescribable, continued for more than three hours, and all the time we were

being driven forward at fierce speed. Then suddenly, as if growning weary of its

frantic exertions, the wind began to lessen its fury and by degrees to die down.

At last we were in prefect calm. The fog mist had also disappeared, and before

us lay an iceless channel perhaps ten or fifteen miles wide with a few icebergs

far away to our right, and an intermittent archipelago of smaller ones to the

left. I watched my father closely, determined to remain silent until he spoke.

Presently he untied the rope from his waist and, without saying a word, began

working the pumps, which fortunately were not demaged, relieving the sloop of

the water it had shipped in the madness of the storm. He put up the sloop's

sails as calmly as if casting a fishing-net, and then remarked that we were

ready for a favoring wind when it came. His courage and persistence were truly

remarkable. On investigation we found less than one-third of our provisions

remaining, while to our utter dismay, we discovered that our water-casks had

been swept overboard during the violent plungings of our boat. Two of our

water-casks were in the main hold, both were empty. We had a fair supply of

food, but no fresh water. I realized at once the awfulness of our position.

Presently I was seized with a consuming thirst. "It is indeed bad,"

remarked my father. "However, let us dry our bedraggled clothing, for we

are soaked to the skin. Trust to the god Odin, my son. Do not give up

hope." The sun was beating down slantingly, as if we were in a southern

latitude, instead of in the far Northland. It was swinging around, its orbit

ever visible and rising higher and higher each day, frequently mistcovered, yet

always peering through the lacework of clouds like some fretful eye of fate,

guarding the misterious Northland and jealously watching the pranks of man. Far

to our right the rays decking the prisms of icebergs were gorgeous. Their

reflections emitted flashes of garnet, of diamond, of sapphire. A pyrotechnic

panorama of countless colors and shapes, while below could be seen the

green-tinted sea, and above, the purple sky.

PART

THREE: BEYOND THE NORTH WIND I tried to forget my thirst by busying myself with

bringing up some food and an empty vessel from the hold. Reaching over the

side-rail, I filled the vessel with water for the purpose of laving my hands and

face. To my astonishment, when the water came in contact with my lips, I could

taste no salt. I was startled by the discovery. "Father!" I fairly

gasped, "the water, the water; it is fresh!" "What, Olaf?"

exclaimed my father, glancing hastily around. "Surely you are mistaken.

There is no land. You are going mad." "But taste it!" I cried.

And thus we made the discovery that the water was indeed fresh, absolutely so,

without the least briny taste or even the suspicion of a salty flavor. We

forthwith filled our two remaining water-casks, and my father declared it was a

heavenly dispensation of mercy from the gods Odin and Thor. We were almost

beside ourselves with joy, but hunger bade us end our enforced fast. Now that we

had found fresh water in the open sea, what might we not expect in this strange

latitude where ship had never before sailed and the splash of an oar had never

been heard[Footnote]? [Footnote begin, Italic] In vol.I, page 196, Nansen

writes: "It is a peculiar phenomenon, - this dead water. We had at present

a better opportunity of studying it than we desired. It occures where a surface

layer of fresh water rests upon the salt water of the sea, and this fresh water

is carried along with the ship gliding on the heavier sea beneath it as if on a

fixed foundation. The difference between two strata was in this case so great

that while we had drinking water on the surface, the water we got from the

bottom cock of the engine-room was far too salt to be used for the boiler."

[Footnote end, No Italic] We had scarcely appeased our hunger when a breeze

began filling the idle sails, and, glancing at the compass, we found the

northern point pressing hard against the glass. In response to my surprise, my

father said: "I have heard of this before; it is what they call the dipping

of the needle." We loosened the compass and turned it at right angles with

the surface of the sea before its point would free itself from the glass and

point according to unmolested attraction. It shifted uneasily, and seemed as

unsteady as a drunken man, but finally pointed a course. Before this we thought

the wind was carrying us north by northwest, but, with the needle free, we

discovered, if it could be relied upon, that we were sailing slightly north by

northeast. Our course, however, was ever tending northward[Footnote]. [Footnote

begin, Italic] In volume II, pages 18 and 19, Nansen writes about the

inclination of the needle. Speaking of Johnson, his aide: "One day - it was

November 24th - he came in to supper a little after six o'clock, quite alarmed,

and said: 'There has just been a singular inclination of the needle in twenty

four degrees. And remarkably enough, its northern extremity pointed to the

east.'" We again find in Peary's first voyage - page 67, - the following:

"It had been observed that from the moment they had entered Lancaster

Sound, the motion of the compass needle was very sluggish, and both this and its

deviation increased as they progressed to the westward, and continued to do so

in descending this inlet. Having reached latitude 73 degrees, they witnessed for

the first time the curious phenomenon of the directive power of the needle

becoming so weak as to be completely overcome by the attraction of the ship, so

that the needle might now be said to point to the north pole of the ship."

[Footnote end, No Italic] The sea was serenely smooth, with hardly a choppy

wave, and the wind brisk and exhilarating. The sun's rays, while striking us

aslant, furnished tranquil warmth. And thus time wore on day after day, and we

found from the record in our log-book, we had been sailing eleven days since the

storm in the open sea. By strictest economy, our food was holding out fairly

well, but beginning to run low. In the meantime, one of our casks of water had

been exhausted, and my father said: "We will fill it again." But, to

our dismay, we found the water was now as salt as in the region of the Lofoden

Islands off the coast of Norway. This necessitated our being extremely careful

of the remaining cask. I found myself wanting to sleep much of the time; whehter

it was the effect of the exciting experience of sailing in unknown waters, or

the relaxation from the awful excitement incident to our adventure in a storm at

sea, or due to want of food, I could not say. I frequently lay down on the

bunker of our little sloop, and looked far up into blue dome of the sky; and,

notwithstanding the sun was shining far away in the east, I always saw a single

star overhead. For several days, when I looked for this star, it was always

there directly above us. It was now, according to our reckoning, aboout the

first of August. The sun was high in the heavens, and was so bright that I could

no longer see the one lone star that attracted my attention a few days earlier.

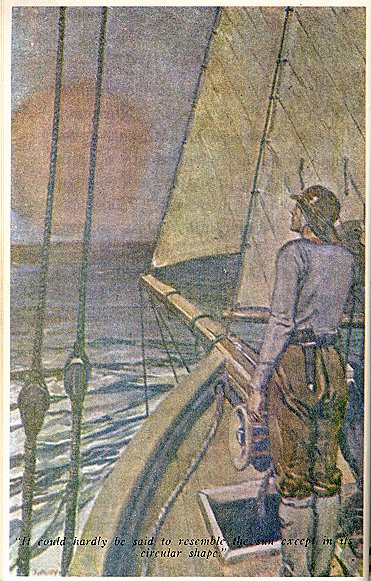

One day about this time, my father startled me by calling my attention to a

novel sight far in front of us, almost at the horison. "It is a mock

sun," exclaimed my father. "I have read of them; it is called a

reflection or mirage. It will soon pass away." But this dull-red, false

sun, as we supposed it to be, did not pass away for several hours; and while we

were unconscious of its emitting any rays of light, still there was no time

thereafter when we could not sweet the horizon and locate the illumination of

the so-called false sun, during a period of at least twelve hours out of every

twenty-four. Clouds and mists would at times almost, but never entirely, hide

its location. Gradually it seemed to climb higher in the horizon of the

uncertain purply sky as we advanced. It could hardly be said to resemble the

sun, except in its circular shape, and when not obscured by clouds or the ocean

mists, it had a hazy-red, bronzed appearance, which would change to a white like

a luminous cloud, as if reflecting some greater light beyond. We finally agreed

in our discussion of this smoky furnace-colored sun, that, whatever the cause of

the phenomenon, it was not a reflection of our sun, but a planet of some sort -

a reality[Footnote]. [Footnote begin, Italic] Nansen, on page 394, says:

"Today another noteworthy thing happened, which was that about midday we

saw the sun, or to be more correct, an image of the sun, for it was only a

mirage. A peculiar impression was produced by the sight of that glowing fire lit

just above the outermost edge of the ice. According to the enthusiastic

descriptions given by many Arctic travelers of the first appearance of this god

of life after the long winter night, the impression ought to be one of jubilant

excitement; but it was not so in my case. We had not expected to see it for some

days yet, so that my feeling was rather one of pain, of disappointment, that we

must have drifted farther south than we thought. So it was with pleasure I soon

discovered that it could not be the sun itself. The mirage was at first a

flattened-out, glowing red streak of fire on the horizon; later there were two

streaks, the one above the other, with a dark space between; and from the

maintop I could see four, or even five, such horizontal lines directly over one

another, all of equal length, as if one could only imagine a square, dull-red

sun, with horizontal dark streaks across it." [Footnote end, No Italic]

One

day soon after this, I felt exceedingly drowsy, and fell into a sound sleep. But

it seemed that I was almost immediately aroused by my father's vigorous shaking

of me by the shoulder and saying: "Olaf, awaken; there is land in

sight!" I sprang to my feet, and oh! joy unspeakable! There, far in the

distance, yet directly in our path, were lands jutting boldly into the sea. The

shore-line stretched far away to the right of us, as far as the eye could see,

and all along the sandy beach were waves breaking into choppy foam, receding,

then going forward again, ever chanting in monotonous thunder tones the song of

the deep. The banks were covered with trees and vegetation. I cannot express my

feeling of exultation at this discovery. My father stood motionless, with his

hand on the tiller, looking straight ahead, pouring out his heart in thankful

prayer and thanksgiving to the gods Odin and Thor. In the meantime, a net which

we found in the stowage had been cast, and we caught a few fish that materially

added to our dwindling ctock of provisions. The compass, which we had fastened

back in its place, in fear of another storm, was still pointing due north, and

moving on its pivot, just as it had in Stockholm. The dipping of the needle had

ceased. What could this mean? Then, too, our many days of sailing had certainly

carried us far past the North Pole. And yet the needle continued to point north.

We were sorely perplexed, for surely our direction was now south[Footnote].

[Footnote begin, Italic] Peary's first voyage, pages 69 and 70, says: "On

reaching Sir Byam Martin's Island, the nearest to Melville Island, the latitude

of the place of observation was 75 degrees-09'-23'', and the longitude 103

degrees-44'-37''; the dip of the magnetic needle of 88 degrees-25'-58'' west in

the longitude of 91 degrees-48', where the last observations on the shore had

been made, to 165 degrees-50'-09'', cast, at their present station, so that we

had," says Peary, "in sailing over the space included between this two

meridians, crossed immediately northward of the magnetic pole, and had

undoubtedly passed over one of those spots upon the globe where the needle would

have been found to vary 180 degrees, or in other words, where the North Pole

would have pointed to south." [Footnote end, No Italic] We sailed for three

days along the shoreline, then came to the mouth of fjord or river of immence

size. It seemed more like a great bay, and into this we turned our

fishing-craft, the direction being slightly northeast of south. By the

assistance of a fretful wind that came to our aid about twelve hours out of

every twenty-four, we continued to make our way inland, into what afterward

proved to be a mighty river, and which we learned was called by the inhabitants

Hiddekel. We continued our journey for ten days thereafter, and found we had

fortunately attained a distance inland where ocean tides no longer affected the

water, which had become fresh. The discovery came none to soon, for our

remaining cask of water was well-nigh exhausted. We lost no time in replenishing

our casks, and continued to sail farther up the river when the wind was

favourable. Along the banks great forests miles in extent could be seen

stretching away on the shore-line. The trees were of enormous size. We landed

after anchoring near a sandy beach, and waded ashore, and were rewarded by

finding a quantity of nuts that were very palatable and satisfying to hunger,

and a welcome change from the monotony of our stock of provisions. It was about

the first Sepetember, over five months, we calculated, since our leave-taking

from Stockholm. Suddenly we were frightened almost out of our wits by hearing in

the far distance the singing of people. Very soon thereafter we discovered a

huge ship gliding down the river directly toward us. Those aboard were singing

in one mighty chorus that, echoing from bank to bank, sounded like a thousand

voices, filling the whole universe with quivering melody. The accompaniment was

played on stringed instruments not unlike our harps. It was a larger ship than

any we had ever seen, and was differently constructed[Footnote]. [Footnote

begin, Italic] Asiatic Mythology, - page 240, "Paradise Found" - from

translation by Sayce, in a book called "Records of the Past", we were

told of a "dwelling" which "the gods created for" the first

human beings, - a dwelling in which they "become great" and

"increased in numbers", and the location of which is described in

words exactly corresponding to those of Iranian, Indian, Chinese, Eddaic and

Aztecan literature; namely, "in the center of the earth". - Warren.

[Footnote end, No Italic] At this particular time our sloop was becalmed, and

not far from the shore. The bank of the river, covered with mammoth trees, rose

up several hundred feet in beautiful fashion. We seemed to be on the edge of

some primeval forest that doubtless stretched far inland. The immence craft

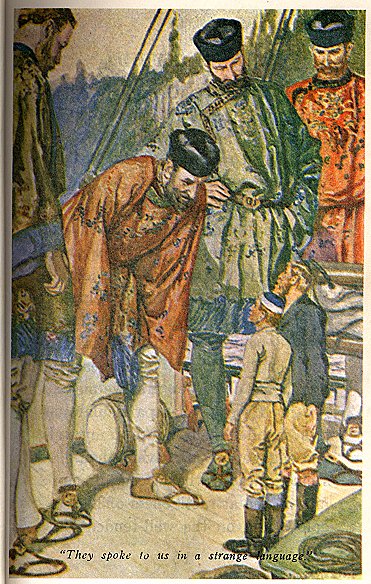

paused, and almost immediately a boat was lowered and six men of gigantic

stature rowed to our little fishing-sloop. They spoke to us in a strange

language. We knew from their manner, however, that they were not unfriendly.

They talked a great deal among themselves, and one of them laughed immoderately,

as though in finding us a queer discovery had been made. One of them spied our

compass, and it seemed to interest them more than any other part of our sloop.

Finally, the leader motioned as if to ask whether we were willing to leave our

craft to go on board their ship. "What say you, my son?" asked my

father. "They cannot do any more than kill us." "They seem to be

kindly disposed," I replied, "although what terrible giants! They must

be the select six of the kingdom's crack regiment. Just look at their great

size." "We may as well go willingly as be taken by force," said

my father, smiling, "for they are certainly able to capture us."

Thereupon he made known, by signs, that we were ready to accompany them. Within

a few minutes we were on board the ship, and half an hour later our little

fishing-craft had been lifted bodily out of the water by a strange sort of hook

and tackle, and set on board as a curiousity. There were several hundred people

on board this, to us, mammoth ship, which we discovered was called "The

Naz," meaning, as we afterward learned, "Pleasure," or to give a

more proper interpretation, "Pleasure Excursion" ship. If my father

and I were curiously observed by the ship's occupants, this strange race of

giants offered us an equal amount of wonderment. There was not a single man

aboard who would not have measured fully twelve feet in height. They all wore

full beards, not particularly long, but seemingly short-cropped. They had mild

and beautiful faces, exceedingly fair, with ruddy complexions. The hair and

beard of some were black, others sandy, and still others yellow. The captain, as

we designated the dignitary in command of the great vessel, was fully a head

taller than any of his companions. The women averaged from ten to eleven feet in

height. Their features were especially regular and refined, while their

complexion was of a most delicate tint heightened by a healthful glow[Footnote].

[Footnote begin, Italic] "According to all procurable data, that spot at

the era of man's appearance upon the stage was in the now lost 'Miocene

continent,' which then surrounded the Arctic Pole. That in that true, original

Eden some of the early generations of men attained to a stature and longevity

unequaled in any countries known to postdiluvian history is by no means

scientifically incredible." - Wm.F.Warren, "Paradise Found,"

p.284. [Footnote end, No Italic] Both men and women seemed to possess that

particular case of manner which we deem a sign of good breeding, and,

notwithstanding their huge statures, there was nothing about them suggesting

awkwardness. As I was a lad in only my nineteenth year, I was doubtless looked

upon as a true Tom Thumb. My father's six feet three did not lift the top of his

head above the waist line of these people. Each one seemed to vie with the

others in extending courtesies and showing kindness to us, but all laughed

heartly, I remember, when they had to improvise chairs for my father and myself

to sit at table. They were richly attired in a costume peculiar to themselves,

and very attractive. The men were clothed in handsomely embroidered tunics of

silk and satin and belted at the waist. They wore knee-breeches and stockings of

a fine texture, while their feet were encased in sandals adorned with gold

buckles. We early discovered that gold was one of the most common metals known,

and that it was used extensively in decoration. Strange as it may seem, neither

my father nor myself felt the least bit of solicitude for our safety. "We

have come into our own," my father said to me. "This is the

fulfillment of the tradition told me by my father and my father's father, and

still back for many generations of our race. This

is, assurely, the land beyond the North Wind." We seemed to make such an

impression on the party that we were given specially into the charge of one of

the men, Jules Galdea, and his wife, for the purpose of being educated in their

language; and we, on our part, were just as eager to learn as they were to

instruct. At the captain's command, the vessel was swung cleverly about, and

began retracing its course up the river. The machinery, while noiseless, was

very powerful. The banks and trees on either side seemed to rush by. The ship's

speed, at tomes, surpassed that of any railroad train on which I have ever

ridden, even here in America. It was wonderful. In the meantime we had lost

sight of the sun's rays, but we found a radiance "within" emanating

from the dull-red sun which had already attracted our attention, now giving out

a white light seemingly from a cloud-bank far away in front of us. It dispensed

a greater light, I should say, than two full moons on the learest night. In twelve hours this cloud of whiteness would pass out

of sight as if eclipsed, and the twelve hours following corresponded with our

night. We early learned that these strange people were worshipers of this great

cloud of night. It was "The Smoky

God" of the "Inner World." The ship was equipped with a mode of

illumination which I now presume was electricity, but neither my father nor

myself were sufficiently skilled in mechanics to understand whence came the

power to operate the ship, or to maintain the soft beautiful lights that

answered the same purpose of our present methods of lighting the streets of our

cities, our houses and places of business. It must be remembered, the time of which write was the

autumn of 1829, and we of the "outside" surface of the earth knew

nothing then, so to speak, of electricity. The electrically surcharged condition

of the air was a constant vitalizer. I never felt better in my life than during

the two years my father and I sojourned on the inside of the earth. To resume my

narrative of events: The ship on which we were sailing came to a stop two days

after we had been taken on board. My father said as nearly as he could judge, we

were directly under Stockholm or London. The city we had reached was called

"Jehu," signifying a seaport town. The houses were large and

beautifully constructed, and quite uniform in appearance, yet without sameness.

The principal occupation of the people appeared to be agriculture; the hillsides

were covered with vineyards, while the valleys were devoted to the growing of

grain. I never saw such a display of gold. It was everywhere. The door-casings

were inlaid and the tables were veneered with sheetings of gold. Domes of the

public buildings were of gold. It was used most generously in the finishings of

the great temples of music. Vegetation grew in lavish exuberance, and fruit of

all kinds possessed the most delicate flavour. Clusters of grapes four and five

feet in length, each grape as large as an orange, and apples larger than a man's

head typified the wonderful growth of all things on the "inside" of

the earth. The great redwood trees of California would be considered mere

underbrush compared with the giant forest trees extending for miles and miles in

all directions. In many directions along the foothills of the mountains vast

herds of cattle were seen during the last day of our travel on the river. We

heard much of a city called "Eden," but were kept at "Jehu"

for an entire year. By the end of that time we had learned to speak fairly well

the language of this strange race of people. Our instructors, Jules Galdea and

his wife, exhibited that was truly commendable. One day an envoy from the Ruler

at "Eden" came to see us, and for two whole days my father and myself

were put through a series of surprising questions. They wished to know from

whence we came, what sort of people dwelt "without," what God we

worshiped, our religious beliefs, the mode of living in our strange land, and a

thousand other things. The compass which we had brought with us attracted

especial attention. My father and I commented between ourselves on the fact that

the compass still pointed north, although we now knew that we had sailed over

the curve or edge of the earth's aperture, and were far along southward on the

"inside" surface of the earth's crust, which, according to my father's

estimate and my own, is about three hundred miles in thickness from the

"inside" to the "outside" surface. Relatively speaking, it

is no thicker than an egg-shell, so that there is almost as much surface on the

"inside" as on the "outside" of the earth. The great

luminous cloud or ball of dull-red fiery - fire-red in the mornings and

evenings, and during the day giving off a beautiful white light, "The Smoky

God," - is seemingly suspended in the center of the great vacuum

"within" the earth, and held to its place by the immutable law of

gravitation, or a repellant atmospheric force, as the case may be. I refer to

the known power that draws or repels with equal force in all directions. The

base of this electrical cloud or central luminary, the seat of the gods, is dark

and non-transparent, save for innumerable small openings, seemingly in the

bottom of the great support or altar of the Deity, upon which "The Smoky

God" rests; and, the lights shining through these many openings twinkle at

night in all their splendor, and seem to be stars, as natural as the stars we

saw shining when in our home at Stockholm, excepting that they appear larger.

"The Smoky God," therefore, with each daily revolution of the earth,

appears to come up in the east and go down in the west the same as does our sun

on the external surface. In reality, the people "within" believe that

"The Smoky God" is the throne of their Jehovah, and is stationary. The

effect of night and day is, therefore, produced by earth's daily rotation. I

have since discovered that the language of the people of the Inner World is much

like the Sanskrit. After we had given an account of ourselves to the emissaries

from the central seat of government of the inner continent, and my father had,

in his crude way, drawn maps, at their request, of the "outside"

surface of the earth, showing the divisions of land and water, and giving the

name of each of the continents, large islands and the oceans, we were taken

overland to the city of "Eden," in a conveyance different from

anything we have in Europe or America. This vehicle was doubtless some

electrical contrivance. It was noiseless, and ran on a single iron rail in

perfect balance. The trip was made at a very high rate of speed. We were carried

up hills and down dales, across valleys and again along the sides of steep

mountains, without any apparent attempt having been made to level the earth as

we do for railroad tracks. The car seats were huge yet comfortable affairs, and

very high above the floor of the car. On the top of each car were high geared

fly wheels lying on their sides, which were so automatically adjusted that, as

the speed of the car increased, the high speed of these fly wheels geometrically

increased. Jules Galdea explained to us that these revolving fan-like wheels on

top of the cars destroyed atmospheric pressure, or what is generally understood

by the term gravitation, and with this force thus destroyed or rendered nugatory

the car is as safe from falling to one side or to other from the single ray

track as if it were in a vacuum; the fly wheels in their rapid revolutions

destrying effectually the so-called power of gravitation, or the force of

atmospheric pressure or whatever potent influence it may be that causes all

unsupported things to fall downward to the earth's surface or to the nearest

point of resistance. The surprise of my father and myself was indescribable

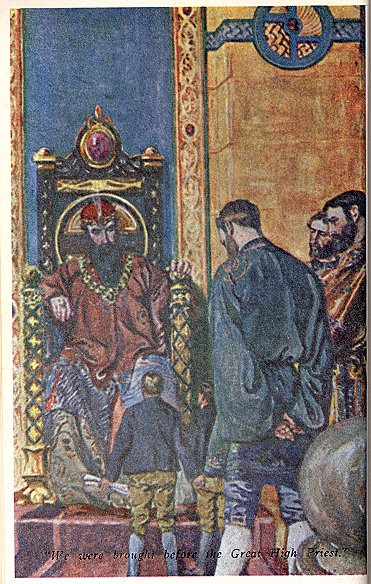

when, amid the regal magnificence of a spacious hall, we were finally brought

before the Great High Priest, ruler over all the land. He was richly robed, and

much taller than those about him, and could not have been less than fourteen or

fifteen feet in height. The immence room in which we were received seemed

finished in solid slabs of gold thickly studded with jewels of amazing

brilliancy. The city of "Eden" is located in what seems to be a

beautiful valley, yet, in fact, it is on the loftiest mountain plateau of the

Inner Continent, several thousand feet higher than any portion of the

surrounding country. It is the most beautiful place I have ever beheld in all my

travels. In this elevated garden all manner of fruits, vines, shrubs, trees, and

flowers grow in riotous profusion. In this garden four rivers have their source

in a mighty artesian fountain. They divide and flow in four directions. This

place is called by inhabitants the "navel of the earth," or the

beginning, "the cradle of the human race." The names of the rivers are

the Euphrates, the Pison, the Gihon, and the Hiddekel[Footnote]. [Footnote

begin, Italic] "And the Lord God planted a garden, and out of the ground

made the Lord God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for

food." - The Book of Genesis. [Footnote end, No Italic] The unexpected

awaited us in this palace of beauty, in the finding of our little fishing-craft.

It had been brought before the High Priest in perfect shape, just as it had been

taken from the waters that day when it was loaded on board the ship by the

people who discovered us on the river more than a year before. We were given an

audience of over two hours with this great dignitary, who seemed kindly disposed

and considerate. He showed himself eagerly interested, asking us numerous

questions, and invariably regarding things about which his emissares had failed

to inquire. At the conclusion of the interview he inquired our pleasure, askng

us whether we wished to remain in his country or if we preferred to return to

the "outer" world, providing it were possible to make a successful

return trip, across the frozen belt barriers that encircle both the northern and

southern openings of the earth. My father replied: "It would please me and

my son to visit your country and see your people, your colleges and palaces of

music and art, your great fields, your wonderful forests of timber; and after we

have had this pleasurable privilege, we should like to try to return to our home

on the 'outside' surface of the earth. This son is my only child, and my good

wife will be weary awaiting our return." "I fear you can never

return," replied the Chief High Priest, "because the way is a most

hazardous one. However, you shall visit the different countries with Jules

Galdea as your escort, and be accorded every courtesy and kindness. Whenever you

are ready to attempt a return voyage, I assure you that your boat which is here

on exhibition shall be put in the waters of the river Heddekel at its mouth, and

we will bid you Jehovah-speed." Thus terminated our only interview with the

High Priest or Ruler of the continent.